Brownfield expansion overtakes greenfield development

Brownfield expansion overtakes greenfield development

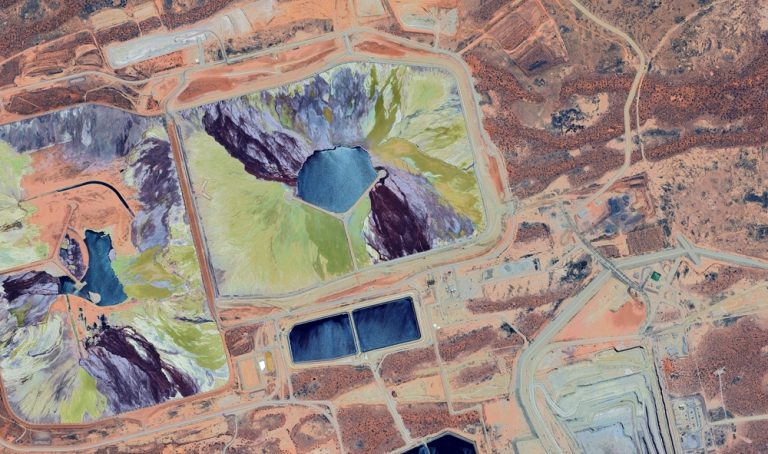

Brownfield development has intensified in recent years and — despite global mineral demand rising faster than supply growth — new mine commissioning has slowed.A new study, led by researchers from The University of Queensland’s Sustainable Minerals Institute (SMI), provides a snapshot of the potential social and environmental costs of this growing trend and the implications for sustainable development.As worldwide demand for minerals surges, mining companies have been doubling down on investment into brownfield development, with the study showing increasing investment in brownfield mining over greenfield sites.This is particularly prevalent in minerals crucial to renewable energy technologies, transport, digital and defence infrastructure — most notably, copper and lithium.Growing demand reflects the rapid uptake of decarbonisation technologies. Such technologies are considered minerally intense. Electric vehicles require about six times the mineral inputs of conventional cars and onshore wind turbines require significantly more minerals than gas-fired plants of similar capacity.While historical mineral production has broadly kept pace with rising demand, projections show demand growing more sharply in the future. For copper and lithium, projected primary supply from announced mining projects will fall short of demand by 2035 under current policy settings, according to the IEA.To maintain supply, the Federal and State Governments continue to reform policy to support mineral exploration and major project development.Last year, the Federal Government proposed amendments to the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act to speed up decision making processes, deliver faster turn arounds and improve bilateral agreements with states and remove duplication for the assessment and approval of projects.Despite growing efforts to streamline approvals for greenfield sites, the global interval between discovery and production has lengthened, now averaging 15.7 years, according to S&P Global.Expansion of brownfield explorationExpanding existing operations has been a cornerstone of many miners’ business models as companies can leverage existing infrastructure and sunk capital.SMI Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining director and lead author Professor Deanna Kemp says 60% of major company exploration budgets in 2024 were at or near existing mines, more than double 2016 levels.“Brownfield mining is an appealing option for mining companies because it maintains production, offers a stronger return on investment, with fewer financial and regulatory risks than establishing new ‘greenfield’ mines, while also deferring the significant costs of closure and rehabilitation,” she said.A snapshot of 366 brownfield sites across 58 countries and16 minerals including critical minerals including cobalt, copper and platinum were used by researchers to understand their social and environmental contexts.The study found that number of new copper mines peaked around 2015, in the early 2000s for iron ore, around 2010–2012 for nickel, and around 2012–2014 for gold. However, since these peaks, and the subsequent decline in the numbers of new mines, production has continued to rise.The research revealed the inverse relationship of rising production with fewer new mines and where output is increasingly concentrated in large, long-life operations for copper, iron ore and nickel — with brownfield capital expenditure being dominated by copper, constituting just under half the total spend.Between 2010 and 2024, expansion dominated industry spending in Australia while other parts of the world saw a gradual increase over the period.According to the researchers, about 80% of the brownfield sites that were studied are located in high risk jurisdictions, facing challenges including water scarcity, poor governance and low press freedom.Regulation of mine expansionThe 2020 destruction of Juukan Gorge, a 47,000-year-old Indigenous cultural heritage site, as part of a legal expansion of an iron ore mine illustrates that brownfield projects can have real and significant costs.“Once a mine has been approved and permitted, expansion is typically a business-as-usual part of developing a mine, even when that expansion changes the original risk of social and environmental impact,” Professor Kemp said.“Brownfield expansion often unfolds incrementally over time, with less public scrutiny: the risk factors involved in each mine site are unique and no-one has really been looking at the scale of growth brownfield mining globally.”The researchers found that more than half of their samples were in locations with multiple complex risk factors like social conflict, fragile ecosystems and weak governance, making it harder for governments and affected communities to respond to the risks presented by these expansions.Mine approval and regulatory standards are usually heavily focused on the beginning of operations by assessing risks and impacts before a mine opens. More recently, there has been an increasing focus on responsible mine closure and land rehabilitation. Both aspects are important, but the research highlights that the way mines expand and extend is becoming more important.“In the ‘middle’ of a mine’s lifespan — when the mine is active there is often less oversight or public focus — changes tend to be regulated, step by step, but the impacts of these expanded operations add up over time,” Professor Kemp said.“More research is needed to quantify the sheer scale of this trend towards greater reliance on brownfield sites, and their cumulative, long-term social and environmental effects.”CSRM research fellow and co-author Dr Julia Loginova says that given that capital is flowing into brownfields, regulatory and academic scrutiny should be moving there as well.“Brownfield sites may be the fastest and economically attractive way to meet rising mineral demand, but it is important to anticipate and manage pressures and long-term liabilities, that’s why further research in this space is very much needed, because there is still a fundamental knowledge gap,” she said.“There is a significant opportunity for interdisciplinary research to better understand scale and impacts, to support improved practice in the sector.”