Importance of mine rehabilitation

New insights drawn from CRC TiME, CSIRO and mining industry databases project that around 240 mines are expected to approach closure in Australia by 2040.

It’s important to note that mine closure and post-mine transition activities, including land rehabilitation as well as workforce planning, accomplish optimal environmental, social and economic outcomes.

The Australian Mining Review spoke with CRC TiME chief executive Dr Guy Boggs about the impact mine closure has on local communities as well as the process involved in rehabilitating a mine.

Part of the Federal Government’s flagship Cooperative Research Centre Program, CRC TiME is a research organisation dedicated to examining and helping transform what happens economically, environmentally, socially and culturally after a mine closes and operations cease.

Impact on Communities

Determining the use of a mine once it’s closed remains a challenge in the mining industry with the optimal use of the mine site varying based on factors such as location, community values and infrastructure.

“The first thing to recognise is that mines change communities,” Dr Boggs said.

“They create jobs, they create new infrastructure, and they’ll have permanent or transitory infrastructure for those communities.

“One of the first things we need to say is ‘what are the future economic opportunities beyond the mine, what do they look like for this region and what sort of implications do they have for the workforce that currently exists in that community’.”

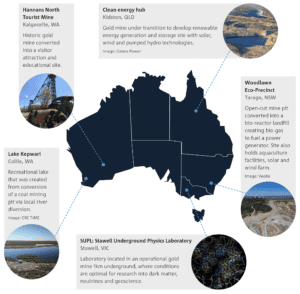

One such community where a lot of work is happening at the moment is in Collie, WA, where the State government is doing a lot of work to attract investment into that town to stimulate new economic opportunities and workforce development.

But there are still implications for what sort of jobs are created as part of these new industries and how they fit with the current skills – or even if there’s a need for retraining.

“Most of our mines occur on the Indigenous estate and all should have a relationship to First Nations communities,” Dr Boggs said.

“For First Nations communities, the cultural healing process that can be achieved through really great rehabilitation projects is incredibly valuable and important.

“We’re finding in a lot of these closure projects, particularly the closure of mines that may have been authorised in a previous environment decades ago, might not reflect our values of today.

As every community is different, CRC TiME is researching how to understand the communities that a mine is operating in.

Mine Rehabilitation Process

The process of planning to close a mine should begin before the initial design of the mine.

As every resource is finite, it might be the market that causes a mine to close or exhaustion of the resource or the ore body.

“We need to be planning for closure from well and truly before the mine has started,” Dr Boggs said.

“It’s important to start before the mine is even approved because it will affect how the mine is designed.

“Where the infrastructure is located or how the pit is designed might be influenced by the potential legacy of the mine.”

For example, if the post-mine future use is as a pumped hydro storage facility, then the mine could be designed differently to enable it to catch water in a particular way, or the energy infrastructure could be built in a specific way so that it can be repurposed at closure.

Mine closure planning and delivery activities, including the creation of final landforms and rehabilitation, occur over the life of a mine.

Once mining is complete, intense closure activities, including the removal or transfer of mine infrastructure and other activities occur.

When the mine goes into closure process, the stages of rehabilitating the site and the landforms (backfilling pits) becomes a part of that process.

The aim is for the workforce to transition to new opportunities as the mine goes from operating to closure.

Over time, once rehabilitation and other activities are complete, the aim is for land to be available for new use.

Careful Closure of a Mine

As with everything, there are both positives and negatives to mine rehabilitation as well as what happens after mining ends.

“One of the issues — and I’m not underestimating how important it is — is we know that mining changes communities and changes landscapes,” Dr Boggs said.

“When it comes to community, at the end of closure, there can be negative aspects associated with that.

“We will always need research and continual thinking about how we are minimising those impacts.

“We want to have a world-leading resources sector and, in the current climate, making sure that we meet our ESG commitments and are show up as responsible miners.

“We need to be able to demonstrate that we can rehabilitate, close and transition mines to a positive state at the end of it.

“From a risk management perspective, it’s really important that we do a good job to make sure that mining is trusted.”

Dr Boggs then went on to add that innovation plays a key role in repurposing mining assets.

“We see land competition, particularly in this energy transition, and we’re seeing new elements of competition for land access between the mining industry and other sectors,” he said.

“Obviously, the closure process is a wonderful step where different sectors can start to connect, leading to mined land becoming part of a future energy project or integrated into agricultural projects.

“The other thing that we haven’t previously recognised and, which is really important to Australia, is that we’re seeing competition for land in areas we haven’t seen before.

“So there’s a great opportunity here – if we solve the rehabilitation closure issues – to get greater opportunity for land repurposing, reuse and shared use.”