Deep sea mining will happen whether we like it or not

Virtue-based legislation comes with a storied history.

In 1927, Al Capone’s liquor operations were generating an estimated US$60m per year, roughly US$873m in today’s dollars, in revenue.

The secret to his success? The fact that the operations were outlawed, not regulated.

Originally implemented to rid society of what the temperance movement saw as alcohol-driven problems, prohibition instead triggered a boom in alcohol sales as well as the crimes that came with the now illegal and unregulated industry.

By 1921, prohibition’s second year, the homicide rate in America had risen 19% to its highest rate ever recorded by that time.

In addition to a swell in organised crime, drinking became riskier, as producers made more potent and thus more dangerous liquor. During prohibition, the potency of spirits rose between 50-100% compared to previous levels.

Like the gangsters of the 1920s, we may soon see a new wave of rebels enter deep sea mining.

The legalities of deep sea mining depend entirely on where an operation is located and the company’s country of origin.

Mining that occurs within a country’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) — extending up to 200 nautical miles from the shore — is subject to that country’s laws and regulations, just like land-based mining.

But when an operation truly reaches the deep, the regulations become murky.

Beyond the EEZ is what the United Nations (UN) defines as the “Area”. The Area is governed by the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which entrusts regulation to the International Seabed Authority (ISA).

The ISA is responsible for managing, licensing and regulating deep sea mining in international waters for its 186 signatories. Notably, signatures from major players like the US are absent.

At present, the ISA is tasked with issuing exploration licenses and developing rules for environmental protection, reporting, royalties and administrative oversight.

These rules have still yet to be defined.

This leaves an abyssal lack of clarity for the future of deep sea mining. How will mining be governed if such significant players aren’t held to the laws of the sea? How do we move forward if the laws of the sea are not delineated?

“This would be a chance to regulate something before it was done, which we aren’t usually able to do,” A&O Shearman partner Lisa Koch said.

“In the current geopolitical climate there’s a risk that a moratorium or a delay in finalising exploitation regulations won’t stop deep sea mining occurring,” Corrs Chambers Westgarth partner Jo Feldman said.

“But it may stop it from being conducted in a regulated manner, sustainably and safely, to a global standard. That is a significant risk now as we are moving into an incredibly fragmented geopolitical landscape.

“It’s perhaps unwise to forego a chance to have international standards because it leaves a vacuum that people may attempt to fill lawfully or otherwise.”

In April, the US issued an executive order, Unleashing America’s Offshore Critical Minerals and Resources, as part of a broader effort to secure reliable domestic supplies of critical minerals.

The order establishes a US policy to “to advance US leadership in seabed mineral development”.

Because the US has not ratified UNCLOS, it cannot sponsor companies seeking ISA contracts. Instead, the country is using its own methods.

The Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act, enacted in 1980 prior to the establishment of the ISA, authorised the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to regulate deep-seabed mining activities, exploration and commercial recovery, of US citizens in areas beyond national jurisdiction.

Now, the executive order directs NOAA to “expedite the process for reviewing and issuing seabed mineral exploration licenses and commercial recovery permits” in areas beyond national jurisdiction.

Following the executive order, The Metals Company USA applied for two exploration licenses and one commercial recovery permit under this framework.

With a mining code still yet to be established and with the blessing of US President Donald Trump, the path forward for deep sea mining now seems to run entirely through the countries that operate outside of the ISA’s regulations.

Because the US’ position sits entirely outside the global regime, there are few venues to contest such actions. Even rulings from the few international tribunals could vary, further confusing the issue.

A broad coalition — made up of environmental NGOs, multinational companies and countries across the world — has called for a moratorium on deep sea mining with the goal of preventing extraction until the ISA finalises a mining code and sufficient scientific evidence is established.

But this pause paired with a patchwork regulatory approach introduces significant risk: without global consensus, rogue actors can exploit regulatory gaps, proliferating unregulated mining in sensitive areas with little oversight.

A moratorium may simply drive players to operate outside of international regulatory frameworks, as evidenced by recent efforts from the US.

More mining, less oversight

This brings us to the law of unintended consequences. Established in 1936 by economist Robert K Merton, unintended consequences can be attributed to ignorance, error, short-term interests and the influence of dominant values.

History offers countless examples.

In the autumn of 1871, the US went up in flames. Four of the most destructive and legendary fires burned along Lake Michigan on October 8, separated only by a few hundred kilometers: the Great Chicago Fire, the Peshtigo fire, the Great Michigan fire and the Port Huron fire.

The Peshtigo fire remains the deadliest wildfire in recorded history.

As public concern grew, conservationists urged the US government to set aside national forest reserves. In the early 1900s, the US Forest Service was established and given control over these national forests.

As a series of devastating fires burned in 1910, the US Forest Service tasked itself with preventing fires and suppressing any as quickly as possible.

Although briefly successful — possibly due to the sheer volume of resources poured into the effort — with a lack of fire, dense underbrush proliferated the forest floor. As a result, when fires did occur, they burned stronger and longer.

Forest ecology now recognises the necessity of prescribed burning, as it maintains healthy stand density, reduces fuel loads and propagates fire-dependent species.

This isn’t to say that reform and regulation should be avoided entirely, but that well-intentioned interventions can amplify the very harm they seek to prevent.

A poorly designed moratorium on deep-sea mining could, similarly, create conditions for unregulated exploitation. Although this may very well be why a decision from the ISA keeps ticking further down the timeline.

Why deep sea mining?

Proponents of deep sea mining position it a strategic necessity rather than an environmental gamble.

Polymetallic nodules — potato-sized rocks found at depths of 4-6km — are rich in manganese, nickel, cobalt and copper. These are considered critical minerals across the world that are in part needed to support green technologies and the energy transition.

For nickel, cobalt and copper in particular, there are mounting concerns that the world may eventually face a lack of supply. Control over both mining and processing is highly concentrated. In many cases, production has become cost-prohibitive or unprofitable under unsupportive price environments.

With declining ore grades and rising costs for land-based mines, a pathway towards a future with ample supply of these materials is unclear. Although recycling will hopefully make up a large portion of the solution, we have yet to reach a stage where it is the only answer.

The dilemma is striking: a multi-trillion-dollar industry, poised to solve some of our critical minerals concerns, sits in one of the planet’s most sensitive and underexplored biomes.

History offers a warning: whether dealing with alcohol, fire or now the deep sea, regulation can backfire when it fails to account for the breadth human incentives.

Prohibition didn’t end drinking — it drove it underground. Fire suppression didn’t end wildfires — it kept the lid on only temporarily.

The same dynamic could repeat in the deep sea: broad restrictions without realistic alternatives invite unbridled activity.

The challenge for policymakers is to regulate before the boom, not after the dust settles.

As policymakers consider how best to govern the deep sea, we walk on the narrow line of virtue, always at risk of tipping into vice on either side.

A spectrum of practices

One argument for legalising deep sea mining is that it opens up entry for ‘good players’ that will abide by and help strengthen regulation.

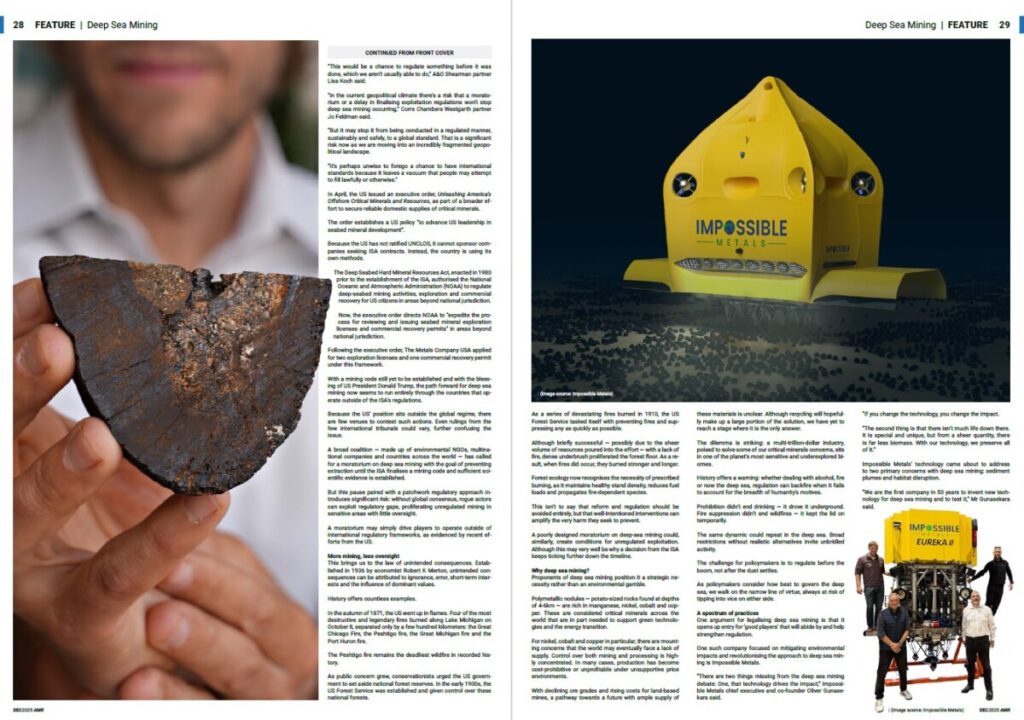

One such company focused on mitigating environmental impacts and revolutionising the approach to deep sea mining is Impossible Metals.

“There are two things missing from the deep sea mining debate: One, that technology drives the impact,” Impossible Metals chief executive and co-founder Oliver Gunasekara said.

“If you change the technology, you change the impact.

“The second thing is that there isn’t much life down there. It is special and unique, but from a sheer quantity, there is far less biomass. With our technology, we preserve all of it.”

Impossible Metals’ technology came about to address to two primary concerns with deep sea mining: sediment plumes and habitat disruption.

“We are the first company in 50 years to invent new technology for deep sea mining and to test it,” Mr Gunasekara said.

“These nodules were discovered more than 150 years ago.

“We looked at what technology we could leverage or invent that was feasible today that wasn’t 50 years ago when people first created the architecture [for deep sea mining].”

Out of this, the Eureka collection system was born.

The system utilises underwater robots, autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), launched from the ship to the seafloor to collect polymetallic nodules.

The primary differentiators of this system, when compared to the dredging tractors, is that it does not create a sediment plume and it preserves biodiversity due to its selective harvesting.

The robots don’t touch down on the seafloor like traditional dredgers, rather they hover and use arms to collect the nodules. The arms rely on cameras and algorithms to collect nodules while avoiding visible life.

“The AUVs run AI algorithms looking at the seabed floor as they hover and move over the seabed,” Mr Gunasekara said.

“They are looking for three things: the actual seabed itself, the polymetallic nodules, and anything else. Anything else we assume is a form of life.”

The AUV will put a quarantine area around any visible life, so collection will not happen in those areas.

The cameras can see anything from about 1mm or larger, according to Impossible Metals. They cannot detect microscopic life, like bacteria and single cell organisms.

“The vast majority of life down there is microscopic, so to mitigate the harm and the risk of species being extinct, we use selective collection,” Mr Gunasekara said.

“In our current model, the robot is programmed to only remove about 40% of the nodules, so 60% of the nodules by weight are left behind.”

Once the robot is full, it will ascend to the ship and offload the nodules into storage. Then, the battery is swapped and any maintenance is performed before the AUV is redeployed.

The full collection cycle would repeat about every four hours, with ships travelling between the processing plant and mining zones while the fleet of AUVs continue collecting.

Compare this method with those used by The Metals Company, and there are notable variations.

The Metals Company uses more traditional methods, relying on machines the size of trucks to land on the seafloor and scoop up nodules.

Detractors, such as the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition, argue these methods create significant sediment plumes and drive biodiversity loss.

The Metals Company’s own research maintains that sediment plumes are created with their extraction method. However, modelling from the company’s wholly owned subsidiary Nauru Ocean Resources (NORI) suggests the plumes are limited to a few kilometres, rather than spreading hundreds of kilometres.

The Deep Sea Conservation Coalition advocates for a moratorium on deep sea mining, the adoption of seabed mining regulations for exploitation and the issuing of exploitation and new exploration contracts until key conditions are met.

This includes ensuring the risks are comprehensively understood, acceptable management pathways are clearly demonstrated, there is an established framework for consultation with Indigenous peoples, alternative sources to produce metals and fully explored and applied, public consultation mechanisms are in place and public support is established, and the ISA structure and function is reformed.

The Metals Company and the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition did not respond to The AMR’s requests for comment.

While some see resources, information or time as critically lacking, the depth of knowledge to be gained from existing industry offers a pathway towards progress for the deep sea mining debate.

“What helps human beings survive as a species is our endless ability to innovate and improve and find new and better ways to do things and the mining industry is a classic example of that – it has developed really sophisticated ESG practices,” Ms Feldman said.

“That’s why it’s so important the mining sector engages in the deep sea mining discussion, because it has expertise about best practice to bring to the conversation.

“The more people engage, especially people with world class expertise, the better chance there is to have a fulsome discussion about whether deep sea mining can be done sustainably with the development of a strong and high standard regulatory regime, rather than watching a race to the bottom in terms of standards the market will tolerate.”