BROKEN LINKS: Fixing Australia’s mining supply chain

When ship hits the fan

With supply chains facing ongoing severe disruptions, such as global pandemics, climate events, floods, bushfires, hostility in the Red Sea, industrial action at shipping ports, ongoing military conflicts and more, the downstream effect on businesses, consumers and the global mining industry are significant.

The Australian Mining Review speaks with Dr Elizabeth Jackson, Associate Professor of Supply Chain Management at Curtin University, about the current state of global and Australian supply chains, including the big issues and big trends facing these complex logistics systems, as well as how they impact our mining sector.

Sustainable supply chains

Q&A with Dr Elizabeth Jackson, Associate Professor of Supply Chain Management at Curtin University

AMR: Can you give us a brief overview of the disruptions that have been happening to the global supply chain over the last four to five years?

EJ: Everything in the commercial world and supply chain world seemed to be going smoothly until the COVID-19 pandemic. It’s the pandemic that has unhinged so many local, national and global supply chains. It’s been a series of events, since the pandemic, that really triggered this cumulative impact on supply chain performance, particularly in Australia, where we’re seeing often catastrophic climate events – for example, massive fires and floods – that are disrupting our supply chains and our ways of manufacturing and transport. Take, for example, the military conflict in Ukraine and the Middle East, related hostility in the Red Sea – these military events seem to have arisen quite close together, comparatively speaking, from before the pandemic. We’ve also seen the frequency of industrial action, as well, and how all of this is linked to financial, economic and societal events. Since the pandemic, we have had cost of living crisis, rising inflation, the lack of availability of products and the rising cost of key business inputs for industries, like agriculture and mining, such as diesel and fuels that power industries. These are all cumulative events and issues. Many of them are not new issues, for example, military conflicts, industrial action and climate changes have been happening for a long time. But it’s the fragility that we experienced during the pandemic, that hasn’t allowed us to catch up with our “business as usual” process and these events have really amplified the impact on how supply chains work in in numerous industries, including mining, agricultural, the primary industries, building and construction – all industries that are very reliant on imports.

AMR: How are supply chains adapting to these disruptions, particularly after the COVID-19 pandemic?

EJ: What we’re seeing globally is supply chains are trying to get shorter. The pandemic made us stop and think about the length of our supply chains and how it adds complexity to the sourcing of goods and services. There was an incident in 2013 in the United Kingdom where horse meat was found in products that were labelled as frozen beef lasagna. This was a watershed moment, putting supply chains under the microscope, in terms of authenticity of products and the trust consumers had in these products. If a mining company orders a drill bit that is made of titanium, it trusts that it is made of titanium and not something else. The spotlight that the COVID-19 pandemic shone on supply chains was how exposed we were to global transport systems. Australia, as an island nation, has prospered from international trade, with many of our local manufacturing industries shut down because of the ease and cost efficiencies of global trade. When our trade links are cut off for any reason, we become very exposed. So the way supply chains are now adapting is that they are looking to source goods from closer to home. There has been a marked shift in reliance, particularly globally, away from Chinese manufacturing. The COVID-19 pandemic really taught the world that we were over reliant on Chinese manufacturing. There is a difference in commercial values between China and Western countries. This really shocked the world and big companies like Apple, for example, have been developing strategies to source from Asia and in particular Southeast Asia. They’ve been going to countries like Vietnam, India, Indonesia and Malaysia to try to be more agile and have more control over where their products are sourced from.

AMR: What role do governments play in Australian supply chains?

EJ: The Federal Government is pivotal to supporting supply chain activity. It might appear on the surface that supply chain activity is a commercial, industrial aspect of society, but supply chains are also reliant on so many government-owned assets, for example, road, port, rail and air transport infrastructure. Government ownership of transport infrastructure is very important. The other important role that governments play is with their licensing and approval. It is being argued amongst industry circles that current government policy is too strict and does not allow businesses to do what businesses need to do to keep being commercial. Policies must enable supply chain growth and development.

AMR: Where does technology fit amongst supply chains right now?

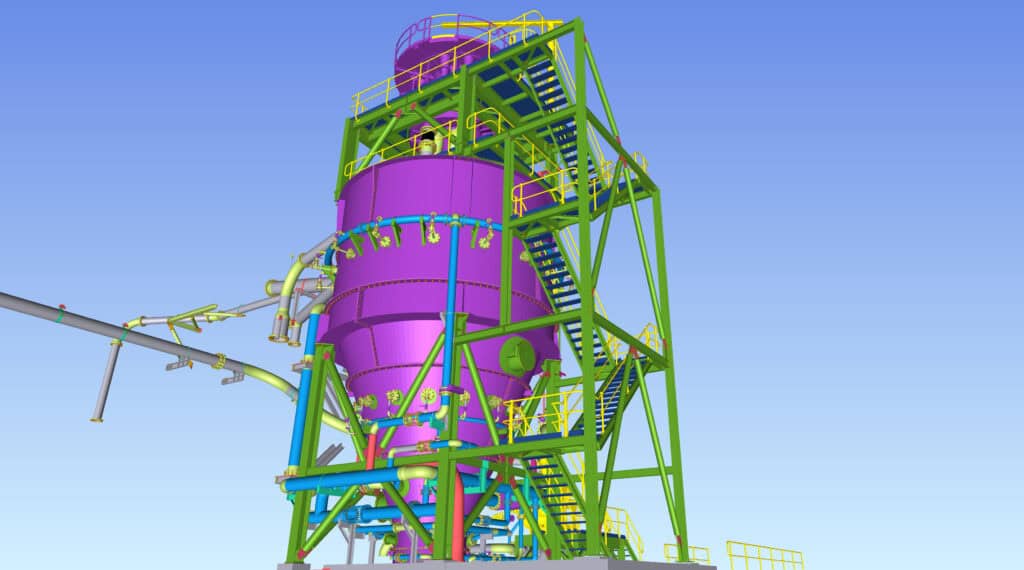

EJ: There are many different types of players in the mining industry – the big players who have big balance sheets, high costs, high revenues and high turnovers. But there are also a lot of smaller businesses and consultancies that are often family businesses, for example, the small family-owned transporting companies that service the mining industry. There is a range of adoption of supply chain technologies to improve the supply chain activity in the mining industry. Big mining businesses are extremely advanced with adopting artificial intelligence, machine learning for predictive maintenance programs with seamless ordering of parts and maintenance requirements through very sophisticated computer technology. For example, the adoption of blockchain technology makes sure that product authenticity flows through the supply chain. This is very important in mining products that are sourced within Australia and countries that don’t have as good and sophisticated environmental and social governance (ESG) around the mining practices that Australia does. When we sell a bag of lithium from Australia, we can be sure that it is a very ethical product. We need to be able to demonstrate that and blockchain is a technology that can do it. There’s another technology that’s coming up in the mining industry called digital twins, a mechanism for simulating scenarios. This is great in supply chains for planning and product delivery – it is value added through the supply chain. Technology is a great investment for doing things better. The downside, however, is that they come at a cost. Against the background of an economic environment with big inflation, big diesel prices and high labour costs, small operators in the mining sector could be criticised for not adopting this technology quickly. But there are very good reasons for that, which are associated with the cost of doing business at present. The adoption of technology in the mining industry is a fascinating case study on what is currently happening and how technology can help, if businesses can afford it at present.

AMR: In what ways can supply chains help improve ESG in mining?

EJ: The big ESG issues at the moment in supply chains nationally is the reporting of Scope Three emissions. These are essentially the emissions that come from supply chains and how goods are moved through the through supply chain. The reporting of Scope Three emissions for mining businesses is becoming increasingly important because of government pledges, not only within Australia, but to the world, that Australia will achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. The Federal Government is starting with big business, which includes some mining companies, amongst others in Australia. They are starting to report on their emissions. Those obligations will filter down to smaller businesses as the emissions reporting policy becomes phased in across all business types. It is important to start with gaining control of Scope Three emissions reporting. The reason that this is the place to start with is because ESG Scope Three emissions reporting provides a framework for not only what a business does, but also what its business partners do. A lot of people think that supply chains is just moving goods from one place to another. The philosophy of supply chains, which a lot of people don’t understand, is that it’s a value creation process. A good example is in the mining industry, where you take something out of the ground as raw material, then change or morph it into a computer chip or a piece of metal. Supply chains are, in the most sophisticated way, the collaboration of businesses that have different roles in the manufacture of a particular good or product. Those businesses share values about what they want to produce for a particular consumer. Another example is that the Mercedes Benz supply chain has very different values than the Toyota supply chain. While they both manufacture vehicles, the Mercedes Benz supply chain will have a very different attitude towards how suppliers and buyers collaborate amongst each other to provide products that are suitable for Mercedes Benz quality vehicles. That’s not to say that Toyota is any worse. They’re just different – they’re servicing different markets. It’s this collaboration between players in supply chains that’s going to be important to Scope Three emissions reporting and the identification of collaborative relationships in supply chains. In the mining industry, the importance of identifying modern slavery in supply chains is a very important part of ESG. Responsibility comes under “Social” and “Governance” in ESG. What we saw was a lot of mining companies and indeed, textile companies, sorting through their global suppliers to make sure that there was no modern slavery in their supply chains. That forced manufacturers and retailers to put their suppliers under the microscope by getting to know their suppliers and clearly communicating to them that modern slavery does not align with Australian values. This is going to be the same with emissions reporting into the future – and all aspects of the E, the S and the G moving forward in supply chains.

AMR: What can Australia do to improve its own internal supply chains?

EJ: The adoption of technology is going to ease pressures. However, as I said earlier, this does come at an enormous cost. It is going to be difficult, particularly the very small organisations, as they’re going to need support. That support will need to come from the government, in terms of investment, but also from industry organisations and peak industry councils through the provision of information and support to their members in facilitating that change. The other one is how governments deal with the progress of industry and commerce – and the investments that they’re prepared to make. It also requires taking a very hard look at the imposition of red tape and compliance that is quite often perceived by industry as being a significant imposition to the progress of commerce right throughout the supply chain. Another one is this idea of shortening supply chains and doing what is possible to invest and purchase inputs either within Australia or closer to home. If there are relationships that can be developed within Australia or closer to home – and I’m thinking Southeast Asia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam. What I’m advocating is risky, it can be expensive but, at the same time, disruptions are also very risky and can do a lot of damage. The closer to home we can have our manufacturing and service provision, it is a good thing. It is making our supply chain more resilient – not only bouncing back from adversity but, what I would say, bouncing forward from adversity. So when there is a disruption, we come out of it in a better state than when we went in.

AMR: How about your suggestions on improving global supply chains?

EJ: I would suggest trying to source closer to home. I understand the difficulties of sourcing within Australia and the costs that it incurs. However, sourcing closer to home in Southeast Asia, looking at supply chains and how they can be made more agile, in terms of where import products are sourced from, I think this is important and quite interesting from the perspective of breaking the rules. Supply chains over the last 30 or 40 years have been working very hard to minimise costs and waste. Waste in the mining industry means, for example, machines sitting idle for too long, stock in warehouses sitting on shelves for too long. Over the last four or five years, with supply chain disruptions that we have been experiencing and the ongoing issues that we’re facing with climate disruptions, the inclement and disruptive weather events are occurring more in remote regions, where a lot of mining companies have their heartbeat, it’s making us realise that these rules that we’ve been working so hard to establish over the last 30 or 40 years may not be so great. We need a little bit of wiggle room and a little bit of fat in our supply chains to buffer against these disruptive events that seem to be occurring more and more frequently. An example is spare parts on a shelf. Many companies have strict KPIs about the length of time spare parts are on the shelf. We have to start easing up on those rules because they’re doing a disservice, in terms of being able to keep our flows of products going so that we can service our customers.

AMR: Which industries or customers are most impacted by supply chain disruptions, apart from mining?

EJ: The building industry, the agriculture industry and the automotive industry. What characterises these industries is that they are desperately reliant on imports from overseas. With the building industry, materials such as wood, iron and steel come from distant markets. With the agriculture industry, materials such as diesel, fertilisers, pesticides and chemicals come from overseas and, perhaps, value-added in Australia. Conflict in the Ukraine had a terrible impact on fertiliser manufacture, for example, not necessarily because that’s where fertiliser comes from but because of the availability of gas, which is a major component of fertiliser manufacture. So it’s not necessarily the product, but it’s the secondary components of the manufacturing processes that are equally important as well. These types of industries are reliant not only on inputs, but processes that go into input manufacture from abroad, which have made us extremely vulnerable.

AMR: What is the impact on Australia if there are further supply chain disruptions?

EJ: As an island nation, we are at the mercy of availability of big cargo ships that import and export our raw materials. We must be able to have access to maritime transport as it’s the only method of transport that can take the quantities of products that we need. It is also the most environmentally responsible method of transport. It is also a method of transport that can take dangerous goods. Air transport is too small, expensive and environmentally unfriendly. When we don’t have access to those ships, we start to get a backlog of product and, when that product is stored for too long, it starts to take up valuable warehouse space. Our supply chains have been engineered, over a 30 or 40 year period, to be extremely precise with how much space we have available for stock. If the stock can’t leave our country, it starts to take up space, leading to a stop in the manufacturing process. This happened during the COVID-19 pandemic and we started to lose money and reputation. A lot of countries come to Australia and engage in commerce with our country because we are a reliable and ethical supplier of raw materials. Brand Australia is extremely powerful. The minute our supply chains fail, we can’t provide our overseas customers with what they need in the quantities and qualities of products that they require. They have become used to Brand Australia. This is why I would argue we need a little bit of fat in the system to keep supplying our overseas customers in the manner that they have been accustomed to.

AMR: On a final note, what are some of the big trends in supply chains now?

EJ: The big trends for supply chains in high-income economies are sustainability, ethical production systems and ethical supply chains that do the right thing by people, the planet and the environment. It is about trying to strike a balance between keeping society in the privilege place that it has become used to but achieving that in a way that is going to meet all those ESG requirements. That is the major challenge at the moment for global supply chains in high income economies. And is that going to happen? I would suggest through the adoption of technology and through support for, particularly, small and small-to-medium-sized enterprises.