Cobre Montana managing director Adrian Griffin spoke to Mark Scott about the company’s new focus on lithium and its recent advancements in the industry.

What is your experience in the industry?

My experience in the industry commenced with Mt Lyell Mining and Railway company, then owners of the Mt Lyell copper mine in Tasmania. I worked there in exploration prior to working for BHP Billiton in iron ore and the Australian Antarctic Division in the 1970s. Like many others I branched out into gold in the early 80s as carbon in pulp (CIP) technology created the opportunity for juniors to become producers.

I spent four years as chief geologist and open pit superintendent with Kia Ora Gold Corporation at Marvel Loch in WA; taking those operations from 10,000 to 80,000 ounces per annum by commissioning a new CIP plant, developing significant open pit operations and construction of an automated heap leach operation.

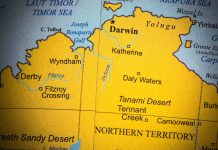

Subsequently I became operations manager for the Independent Resources Group, with mines in Australia (Pine Creek and Nevoria), Indonesia, the Philippines and the US. Following a hostile takeover of Spargos Mining, I took the role of mine manager at Bellevue gold mine which, at the time, was a significant underground producer, second only to Mt Charlotte, all achieved with hand-held mining techniques.

In the mid 90s I became managing director of Preston Resources and gained useful exposure to the nickel industry, pioneering high-pressure-acid-leach, initially by way of banked feasibility of the Marlborough nickel project in north Queensland and later commissioning and operation of the Bulong nickel project.

I was managing director of Dwyka Diamonds with operations in South Africa and founding director of public companies Ferrum Crescent, Northern Minerals, Potash West, Hodges Resources Limited, Reedy Lagoon Corporation and Empire Resources.

My involvement with Cobre Montana (at the time Midwinter Resources) commenced about 2009 with a reverse takeover by way of vending some South African iron ore assets. The GFC, slump in iron ore prices and lack of stability in the South African mining industry made continuing exploration impractical. In 2013 the company diversified into copper/gold in Chile, accompanied by a name change which better reflected its aspirations. Unfortunately, although exploration of its flagship Mantos Grandes deposit was technically successful, it was unlikely to see the near-term production we had hoped for. In 2014 the company turned its focus to a unique opportunity in the lithium industry: extraction of lithium from micas, the ‘lost lithium ore’.

What assets does Cobre Montana hold, and what ventures is the company involved in?

The company has exclusive licensing rights for the extraction of lithium from micas in WA for a period of 25 years; two exclusive licenses that can be used anywhere outside WA; licences bolstered with a technical support agreement with Perth-based technology provider Strategic Metallurgy; 100 per cent of the Ravensthorpe lithium micas project in WA; 80 per cent of the Coolgardie rare metals venture, with partner Focus Minerals; 80 per cent of the Seabrook rare metals venture in WA, with partner Tungsten Mining; a strategic partnership with Pilbara Minerals to investigate lithium micas at Pilgangoora, WA; a strategic partnership with European Metals to investigate lithium micas at Cinovec, Czech Republic; a partnership with SciAps to develop practical, field-based, light-element prospecting techniques; and is negotiating a significant interest in the Greenbushes pegmatite field, with an anticipated closure in January.

Why has Cobre Montana turned its focus to lithium?

The extraction of lithium from lepidolite – a lithium mica that is possibly the most common lithium mineral – has been a long term interest of mine. Indeed it seemed a reasonable extension to work done by Potash West, of which I am chairman, to recover potash from gauconite, a high potassium clay. That process was one of the fertiliser industry’s ‘holy grails’ and it appeared the same could be done to recover lithium, and other rare metals; firstly from lepidolite and then from lithium micas in general.

Deposit identification and sampling was done by Cobre Montana while Strategic Metallurgy, which had done the development work on potash extraction, funded the initial test programs. Testing demonstrated it was easy to obtain clean lepidoite concentrates, concentrates could be readily digested at atmospheric pressure, the process had a very small energy footprint and by-product credits could cover a large proportion of the operating cost.

Lepidolite has historically been discarded by hard-rock lithium miners, which meant a successful metallurgical process could provide access to deposits of the ‘lost ore’, access to dumps of discarded material, and access to current tailings streams where lithium micas are discarded. Potentially there is a lot of material available on a global scale, many occurrences where mining is not required and the processing cost may make production of lithium carbonate – the principal feed material to the lithium battery industry – competitive with the world’s cheapest producers.

The lithium battery industry is expanding more rapidly than most other industries and is largely driven by demand for electric vehicles, projected to rise from current production levels of about 200,000 per annum to 40 million by 2050. Technologically it is difficult to achieve charge densities per unit mass greater than that provided by lithium. The specific chemistry of battery systems will change, but lithium will remain, and be locked into the ever increasing demand cycle.

How did the recent partnership with SciAps come about?

SciAps is a well-respected technology developer and has developed some of the first practical, field-portable laser analysis equipment. One of the great benefits of laser technology in the analytical field is the ability to analyse light elements such as lithium, beryllium and boron. In a geochemical sense, the elements are considered ‘incompatible’ and found associated with some pretty weird rock types that tend to accumulate elements that don’t easily fit into the more common rock-forming minerals. The pegmatites, being targeted as a source of lithium micas by Cobre, are indeed one of those weird rock types.

SciAps was looking for geological materials to test the practical aspects of their light-element analytical equipment, and Cobre was looking for an analytical technique it could use in the field. There was a technical issue to be resolved, and both parties had a need to get a positive outcome, so the partnership is the perfect marriage.

What would portable testing mean for lithium exploration, industry-wide and for Cobre Montana?

By having the ability to analyse the signature elements of lithium pegmatites it will be possible to undertake relatively inexpensive, high-resolution geochemical surveys to identify concealed pegmatites. This will reduce exploration expenditure and allow large areas to be covered very quickly.