Good, old-fashioned hard yakka

From the coal dust-covered Bowen Basin to mud-slick slopes across Southeast Asia — Chris Green has worked in some of the world’s most prominent mining districts.

Born in 1949, Chris grew up on a dairy farm in Aberdeen, Tumut, NSW, with four brothers. His father worked for Thiess as a fitter and turner at their Snowy Mountains operations.

As a teenager, Chris’ mother told his father to “get this boy a job, he’s driving me mad”. Not long after, Chris began his 57 year-long mining career with Morrison Knudsen & Utah McDonald in 1965.

“I was the offsider on a fuel truck, and I used to go up and down, up and down, filling their shovels and everything up on the construction site at dedicated times throughout the shift,” he said.

“There was no quick fill back then, everything was done manually.

“That’s where I started to learn how to operate machinery and I’ll tell you what, if it’s got a steering wheel or steering clutches and a motor, I can operate it.”

Ever since then, two of Chris’s favourite smells became the smell of diesel smoke and the breaking of fresh dirt.

Chris retired for the first time in 2020, but it did not last long. After two years, he was decidedly bored out of his mind and went back to work as a dozer operator across various sites in Queensland, including Curragh coal mine near Blackwater.

“I didn’t like sitting still, I just wanted to keep operating,” Chris said.

The adventure begins

In 1968, as a skilled operator, Chris was offered his first opportunity to work internationally with MK Fluor JV.

“They asked me if I had a passport and they took me to Bougainville in Papua New Guinea,” Chris said.

“When I was working at that site, I raised concerns several times about the safety conditions we were operating in. Things were not regulated nearly as much as they are today, it was even worse in developing countries.”

Chris left PNG after his concerns were not addressed. Less than two weeks later, there was a landslide on the site, in an area known as policeman’s corner, that took the lives of seven operators.

Chris gave the global mining industry another try in 1982, taking up the role of a senior civil supervisor for HTL JV in Nadi, Fiji. This time, he took his wife and three young children with him — the whole family lived, worked and went to school in Fiji for two years.

After his experience in Fiji, Chris ventured back to PNG to work on the Ok Tedi copper and gold mine as a construction supervisor. He was glad to find that safety and regulatory conditions had vastly improved.

“I was an inspector in charge of 158km of road,” Chris said.

“The convoy used to go all the way from the Ok Tedi mine down to the port and I was one of two inspectors. We used to look after all the contractors with realignments and so on.

“Bear in mind, you get 10.5m of rain a year — it’s one of the wettest places on earth — things used to breakdown constantly.”

In 1996, Chris flew to Kalimantan, Borneo, to work with various companies on a variety of civil construction projects for coal and gold mines. This was during a time when headhunting had made a recent resurgence amongst the Dayak tribes of the Indigenous people due to encouragement from the local government for political reasons.

“We used to have to travel through the jungle up the Mahakam River to get to the site where we were putting a new haul road in,” Chris said.

“One day we took a few wrong turns up a couple of different channels that we shouldn’t have. I started to see people on the shore; it was nothing like I’d ever seen in my life.

“I was the only expat on that boat, and I tell you what, when one of the guys turned around to me, pointed at the people in the jungle and said cannibals I nearly jumped out the boat and swam back to Australia.

“That’s when I told them to turn the boat around and I never went back out there again unless I had security with me.

“It was a challenge and a half, but it was remarkable. You often saw orangutans just swinging from tree to tree right above your head.”

The mining industry in Borneo was very poorly regulated at the time and illegal mining was rife. Miners also faced significant resistance from local communities.

“We used to float the coal boats down the river and they occasionally disappeared. We assumed they were stolen because we’d never see them again,” Chris said.

“One night, Dayak tribesmen came into the mine village in Kalimantan and set it on fire. I was the manager in charge of that project. The company got me on a helicopter at two in the morning and straight out of there.”

Back in Australia, Chris worked across a variety of projects beginning with Thiess at the Talbingo Dam from 1968–1972. He then moved on to Thiess’s Greenvale railway line project, which involved the construction of a railway line to transport nickel ore from a mine in Greenvale to the Queensland Nickel refinery in Yabulu, as a leading hand operator.

“I was in gold mines, coal mines, nickel mines, pipelines, road jobs, railway lines, dams and all sorts throughout my career,” Chris said.

In 1975, Chris moved to Blackwater coal mine to take up a role as a dozer operator before moving up to drag line supervisor where he oversaw 15 operators and millions of dollars’ worth of equipment.

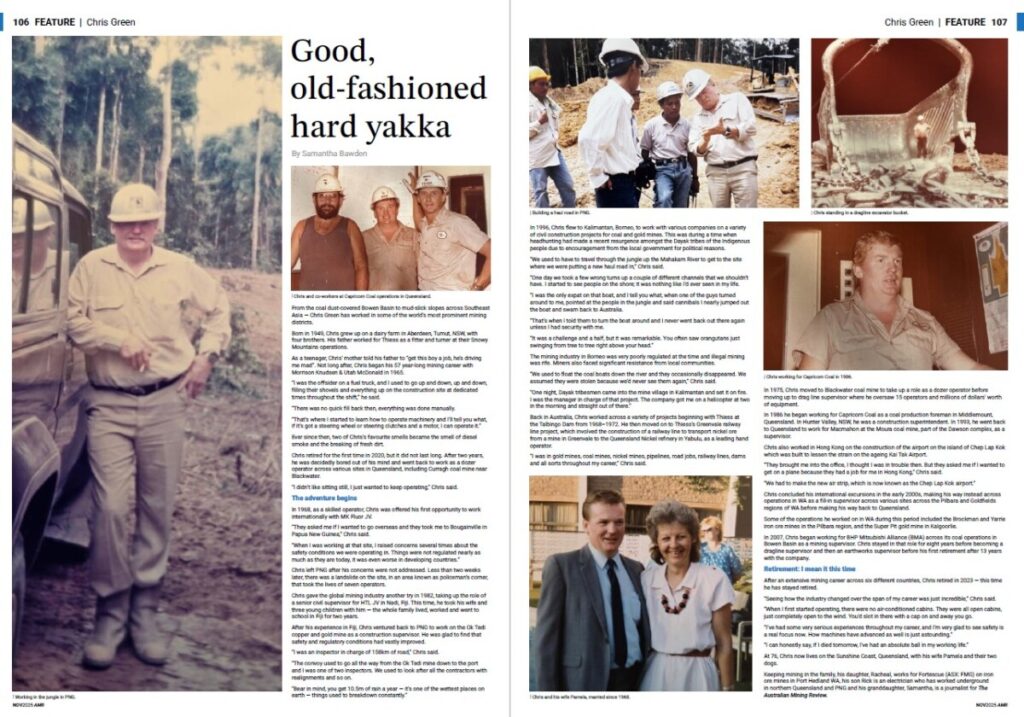

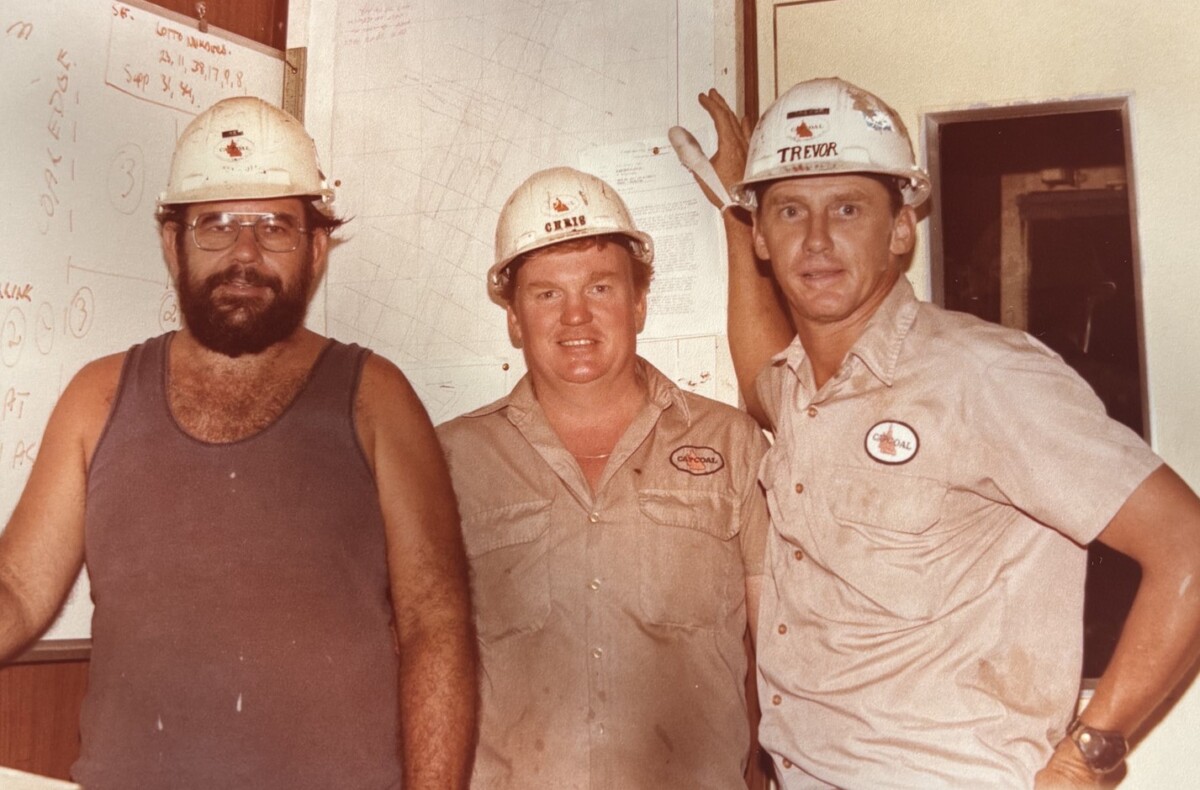

In 1986 he began working for Capricorn Coal as a coal production foreman in Middlemount, Queensland. In Hunter Valley, NSW, he was a construction superintendent. In 1993, he went back to Queensland to work for Macmahon at the Moura coal mine, part of the Dawson complex, as a supervisor.

Chris also worked in Hong Kong on the construction of the airport on the island of Chep Lap Kok which was built to lessen the strain on the ageing Kai Tak Airport.

“They brought me into the office, I thought I was in trouble then. But they asked me if I wanted to get on a plane because they had a job for me in Hong Kong,” Chris said.

“We had to make the new air strip, which is now known as the Chep Lap Kok airport.”

Chris concluded his international excursions in the early 2000s, making his way instead across operations in WA as a fill-in supervisor across various sites across the Pilbara and Goldfields regions of WA before making his way back to Queensland.

Some of the operations he worked on in WA during this period included the Brockman and Yarrie iron ore mines in the Pilbara region, and the Super Pit gold mine in Kalgoorlie.

In 2007, Chris began working for BHP Mitsubishi Alliance (BMA) across its coal operations in Bowen Basin as a mining supervisor. Chris stayed in that role for eight years before becoming a dragline supervisor and then an earthworks supervisor before his first retirement after 13 years with the company.

Retirement: I mean it this time

After an extensive mining career across six different countries, Chris retired in 2023 — this time he has stayed retired.

“Seeing how the industry changed over the span of my career was just incredible,” Chris said.

“When I first started operating, there were no air-conditioned cabins. They were all open cabins, just completely open to the wind. You’d slot in there with a cap on and away you go.

“I’ve had some very serious experiences throughout my career, and I’m very glad to see safety is a real focus now. How machines have advanced as well is just astounding.”

“I can honestly say, if I died tomorrow, I’ve had an absolute ball in my working life.”

At 76, Chris now lives on the Sunshine Coast, Queensland, with his wife Pamela and their two dogs.

Keeping mining in the family, his daughter, Racheal, works for Fortescue (ASX: FMG) on iron ore mines in Port Hedland WA, his son Rick is an electrician who has worked underground in northern Queensland and PNG and his granddaughter, Samantha, is a journalist for The Australian Mining Review.